We Feed The World juxtaposes industrial and traditional farming techniques in ways similar to those used to critique industrial fishing when exploring other foods: tomatoes, sunflowers, eggplants, and onions. According to one expert, natural vegetables are better tasting and more efficient because farmers can reuse the seed, but seed companies are owned by a few companies and are subsidized, so genetically modified seed and hybrid vegetables have become the norm in countries around Europe.

But when the film discusses changes to soy production, it emphasizes not nostalgia for GMO free seed but other consequences of industrialized farming: fewer companies controlling distribution. According to one expert, few foods are GMO free, including animal feed and chocolate. All this food is not sent to countries that need it, so 100,000 die of starvation. One huge food company, Pioneer, is in 120 countries, including China, and their slogan is “We feed the world,” but, according to the spokesperson, the company has no heart and sells to the highest bidder rather than feeding a starving world. This food advocate asserts that 842 million people are malnourished, so “Any child who dies of starvation is murdered and reinforces numbers” he says.

The film shows soy manufacturing as especially problematic in other ways, as well. According to one expert, because they are fed on Brazilian soy, European livestock are, in a sense, eating up the rainforest of Amazonia, causing an ecological imbalance. In Brazil, an area the size of France plus Portugal has been cleared since 1975 while children starve in Somalia, Sudan, and rural Brazil, where women feed their children stone soup. In Northeastern Brazil, water is contaminated, and women can only feed their children goat’s milk once they have outgrown their mothers’ breasts. These rural Brazilians cannot read and write, and now they can grow little food; even though Brazil is one of the largest exporters of soy and one of the richest agrarian states, its people are starving. Europeans import 90% of soy for their livestock from Brazil, the expert explains, since European corn and soy are burned for electricity.

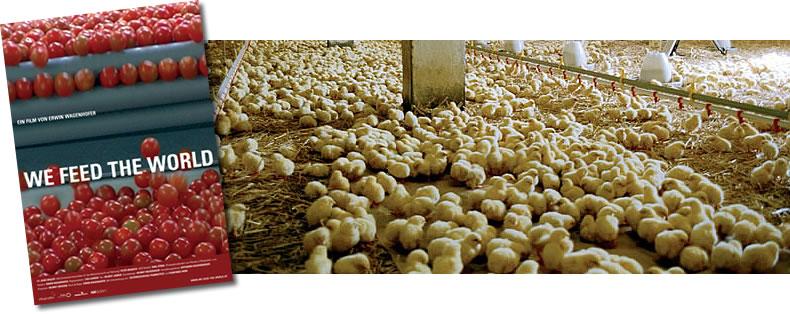

The film attempts to reveal some of the dangers of industrialized chicken and egg production, as well, but it ends with a portrait of Nestle’s CEO and his claim to feed the world. Avene Nestle, the company’s current CEO asserts that “Nature is no longer pitiless” and advocates for GMO food instead of organic, since it will more quickly and readily feed the hungry. Although Nestle explains that his responsibility is to ensure a profitable future for the company and its shareholders, his point about feeding a starving world seems like an answer to the starvation problem broached by the film. The film ends with this portrait, leaving the viewer with mixed reactions to the film’s images of industrialized food production. Instead of the single message and point of view of Gore’s Inconvenient Truth, We Feed the World relies on a series of experts to make its point about the social and environmental consequences of turning food production into a massive industry. Yet the film loses its edge when it ends not with a clear rearticulation of its thesis but with an opposite, contrasting, and conflicting message of a new kind of hope: the hope that with efficiency and high-production counts that include GMO seed and the end of food production as a family business, factory farming can feed the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment