Ecocinema and the City seeks to add to urban ecocinema scholarship by exploring four sections arranged to

highlight the increasing importance nature performs in the city: Evolutionary Myths Under the City, Urban

Eco-Trauma, Urban Nature and Interdependence, and The Sustainable City. The first two sections,

“Evolutionary Myths Under the City” and “Urban Eco-Trauma,” take more traditional ecocinema

approaches and emphasize the city as a dangerous constructed space.

Part I, “Evolutionary Myths Under the City” examines evolutionary narratives of environmental adaptation in

both film noir and documentaries focused on urban sewers and subways. The films explored in our first section,

“Evolutionary Myths Under the City,” call into question the idea of the city as natural and unaffected by human

intervention and illustrate how social and environmental injustices sometimes intertwine. The notion of

displacement from the New Objectivity art movement of the 1920s helps elucidate this de-naturalizing of the city.

As Daniela Fabricius explains, “Displacement can be a way of understanding not only the abyss between a

landscape and how it is represented but also the erosion of the seemingly fixed binaries that separate natural

and manmade environments” (175). “Evolutionary Myths Under the City” explores these fluid binaries as it

focuses on tragic and comic evolutionary narratives. The films explored in this section ask evolutionary

questions about who we are, where we’re going, and which story of ourselves we choose to construct:

a tragic or comic evolutionary narrative.

Chapter 1, “The City, The Sewers, The Underground: Reconstructing Urban Space in Film Noir” examines

the idea of the city as a social and cultural construct through a reading of He Walked by Night (1948). The

film highlights how and why not genetics but social, cultural and historical forces construct “gangsters.” But

what sets the film apart from other noir films is the attention it gives to the urban infrastructure hidden

below its progressive construction. By foregrounding sewers as constructions, escape routes, and seemingly

safe havens for noir characters, the film demystifies what seem like “givens” and calls into question the

idea of the city as natural.

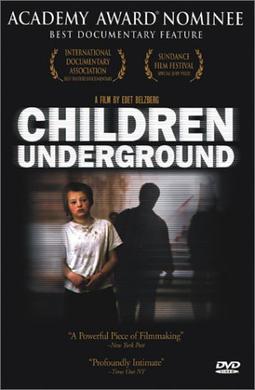

Chapter 2, “Documenting Environmental Adaptation Under the City: Children Underground (2001)” explores

underground constructions from the perspective of homeless children in Children Underground (2001). On the

surface the children in Children Underground have entered an underground that serves as the site of technological

progress where excavation produces not only the means of production—coal and oil, for example—but also

the foundation for the urban infrastructure—sewage and water systems, railways, gas, and lines for

electricity, computers, and phones. They have entered a technology-driven underworld and reconstructed,

domesticated, and humanized it as a home, an ecology in which they can move beyond survival toward

interdependence. Yet because their plight and the home they inhabit are built on both nature and former

dictator Ceausescu’s cultural attitudes, these homeless children also illustrate how social and environmental

injustices sometimes intertwine.